Continuing our ‘In search of secret wildlife’ series, Nina Seale dives into the mysteries surrounding marine ecology and conservation, exploring the dangers that mining and industrial fishing present when so little is known about the potential impact.

We know so little about our ocean, we can’t even guess the number of zeroes we need to measure marine life.

There are currently approximately 200,000 described marine species (about 11 per cent of all described species). But there could be more than 10 million.

However, we do know that the vast accumulation of life which has evolved and flourished in our ocean plays a very important role in how we experience life on land.

Coastal forests such as mangroves provide important protection to terrestrial ecosystems from events such as tsunamis. Image: Jamie Patra CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The role of ocean biodiversity

An example of the effect that losing marine life can have on land can be observed with seagrass meadows. When seagrass meadows are lost, it can affect temperature and sea level, as well as the frequency of storms and hurricanes. More broadly, when coastal ecosystems collapse, there are declines in local fish catch and water quality, as well as increased coastal flooding and harmful algal blooms. In the 2004 tsunami, areas buffered by coastal forests were less damaged than areas without.

But due to the difficulty of studying our planet’s marine diversity, we cannot boast that we understand all the complex relationships between marine life great and small, the seafloor, and the aquatic environment itself.

Sperm whales dive more than 6,000 feet in pursuit of prey and much about their ecology is still unknown, and yet commercial sperm whaling from the early 18th century is estimated to have reduced the global population by approximately 73 per cent. Image © iStock

Mysteries of the ocean

There are many examples of people exploiting ocean resources before understanding the consequences of their activities. One well-known cautionary tale is that of whaling, which has crippled many populations of whales around the world (the pre-whaling population of blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere was about 250,000, and there are now estimated to be fewer than 1,500). The decline in great whale numbers due to whaling is estimated to be at least 66 per cent and perhaps as high as 90 per cent.

So, we already came devastatingly close to losing our whales while having barely scratched the surface of understanding their ecological importance. A 2019 study published an estimate of the economic value of a great whale based on carbon capture, whale watching, and impact on the food chain, at more than USD 2 million.

The ecology of European eels has presented a zoological mystery for thousands of years. Image © iStock

A glass eel, the larval stage of the European eel. Image: Flickr/canopic CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Another example is that of the European eel, which was once an abundant freshwater catch in many areas of Europe and northern Africa but is now a Critically Endangered species. The life history of these eels has proved a mystery for thousands of years (ancient Egyptians believed eels were produced by the sun warming the Nile). Even now as their mysterious origins are becoming known to science, the strangeness of their story is worthy of such a long mystery. It is a fascinating tale of metamorphosis and epic journeys floating thousands of miles between the Sargasso Sea on the Gulf Stream before transforming into finger-length, transparent miniature ‘glass eels’.

However, over the past 40 years, the number of glass eels arriving in Europe has fallen by 95 per cent. Due to the complexity of the eel life cycle and many more mysteries about their ecology we have not yet understood all the reasons for their decline, but it could be due to all manner of human-related activities such as climate change, dams, overfishing, and pesticides.

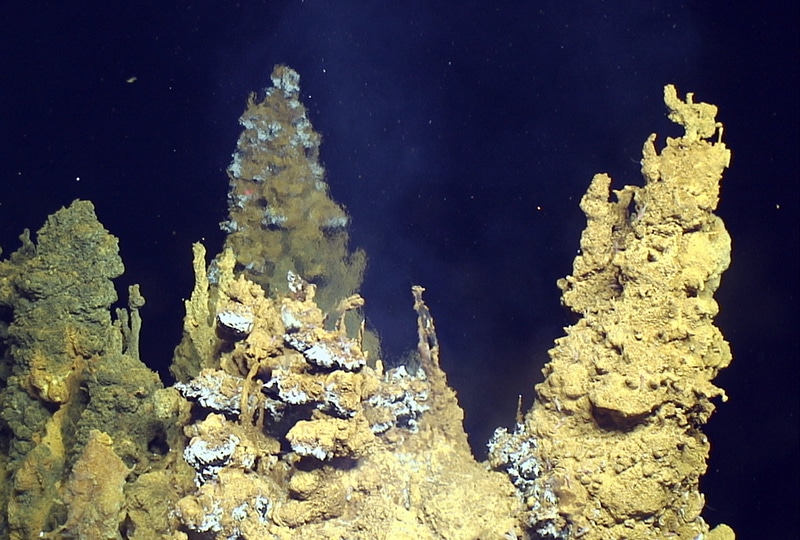

With even such a historically common species as the European eel falling victim to the blind actions of humanity, how can we justify further dangerous actions such as deep-sea mining and trawling? Hydrothermal vents in the deep sea were first described as recently as 1977, with only around 10 per cent of deep ridge habitats having been explored since then. These vents are found between 1,000-4,000 metres deep and have the extraordinary and seemingly inhospitable conditions of temperatures up to 400°C and high acidity. Yet they support vast communities of unique underwater life.

We know so little about the deep seas that practically every expedition unearths a treasure trove of new knowledge, and we have barely scratched the surface.

“Oftentimes when we go on these [deep sea] research cruises, no one has been there before and therefore we’re finding new habitats, we’re finding new species, we’re finding new behaviours. Literally nearly every single research cruise that happens.”

Diva Amon, deep-sea marine biologist

So, we have some idea of the importance of the ocean and the life which depends on it, but do not yet understand it. But as we are still unravelling these many marine mysteries, various vested interests are committed to plundering the ocean’s resources before local communities, scientists, and activists can make a well-researched argument about why we should stop. It is like driving a bulldozer through a pristine rainforest before we have any idea what lives in it.

There are two great threats that both apply here: deep-sea mining, and industrial fishing.

Deep-sea mining presents a strong threat to the complex and largely unknown ecosystems around hydrothermal vents. Image: Submarine Ring of Fire 2014 – Ironman, NSF/NOAA, Jason, WHOI.

Deep-sea mining

Deep-sea mining is the extraction of deep-sea minerals such as the copper, cobalt, nickel and manganese found in deep-sea nodules. The ‘gold-rush’ looming for these minerals is picking up pace with the ever-increasing demand for certain materials used in smartphones and green technologies.

Some of the predicted consequences of deep-sea mining include permanently damaging the unique, slow-growing ecosystems where metallic nodules are found (one study found that an experimentally mined area, once rich with nodules and marine life, was still devoid of fauna 37 years later); destruction of vent chimneys and compressing sediment which will make recovery far less likely; and many other disturbances such as light and noise pollution, trash, and crushing marine organisms. These consequences have been enough to persuade global companies Google, BMW, AB Volvo Group, and Samsung SDI to sign up to a World Wildlife Fund call for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, sending a message about the future of source materials for our cars and smartphones.

There are more than 900 species of squat lobster, this Munidopsis species lives on an active hydrothermal vent and its hairiness is attributed to a bacterial ‘mat’. Image: NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas.

Our partners working on deep-sea conservation, such as the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (DSCC), are calling for a moratorium to temporarily ban deep-sea mining worldwide until the consequences can be considered. We do not know the full extent of the impact, but we do know that there would be severe local impacts on deep-sea life, and that the brunt of consequences for human populations would fall on developing countries, particularly small island nations. Many civil society groups in such nations, such as our partners the Alliance for Solwara Warriors and Bismarck Ramu Group (BRG), have launched opposition to deep-sea mining, but at the same time, governments are seizing the opportunity to lead a new gold rush.

We do not understand the extent of the fallout that this kind of destruction would cause, but even more concerningly, by the time these consequences are made clear, it may be too late for recovery.

Industrial fishing

Lack of knowledge, lack of regulation, lack of responsibility. The vastly unregulated actions of industrial fisheries, especially on the high seas (the parts of the ocean beyond any one country’s jurisdiction), are not just depleting the world’s fish stocks, but also give rise to numerous human rights violations.

“The high seas are a place where anyone can do anything because no one is watching.”

Ian Urbina, journalist

Billions of people rely on marine fisheries for their diets. However, the approach of industrial fisheries is to use excessively destructive practices with little regulation and barely any regard for sustainability, putting the future of this important food source at risk and having a profoundly negative impact on marine ecosystems more broadly. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that 85 per cent of marine fish stocks are either fully exploited or overfished.

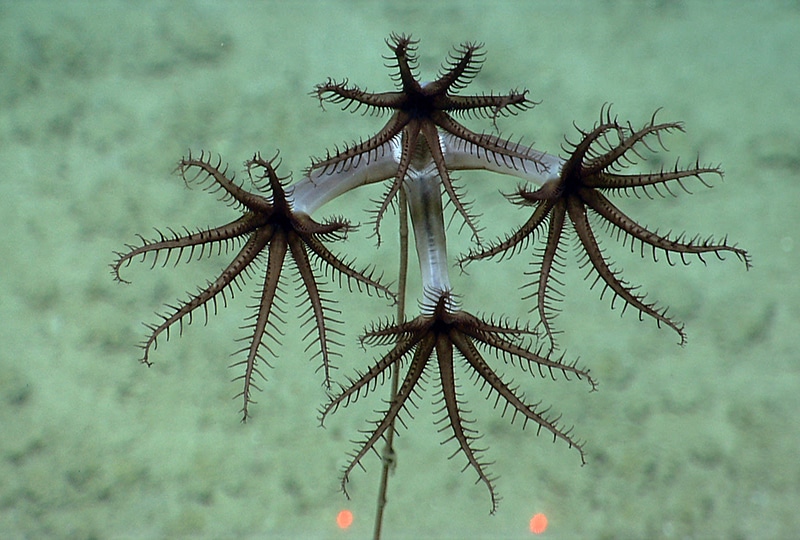

38 million tonnes of sea creatures are unintentionally caught each year and disposed of – 40 per cent of fish catch worldwide. Some of the most damaging practices involve the use of drift nets (long nets suspended from the surface with no specialisation to avoid catching unintended species), gill nets (nets which catch target species by their gills, but are often not used properly and act as drift nets), and bottom trawling (when weighted nets are dragged along the seafloor).

An octocoral in the deep sea. Image: NOAA OKEANOS Explorer Program , 2013 Northeast U. S. Canyons Expedition

Time to change

We rely on our ocean for provisions such as food; regulating services such as coastal protection, carbon storage, and water purification; and cultural services such as recreation and spirituality.

Blind exploitation of our ocean threatens the vital role the ocean plays on our planet and endangers the survival of all life on Earth.

We need to know more. Considering how little we know about our oceans, we can safely guess that we will not know the full extent of the consequences of human activities until they are upon us, and by then, the damage may be too severe for recovery.

Synchronicity Earth’s High and Deep Seas Programme is expanding to help address other overlooked aspects of marine conservation, including some mentioned here such as seagrass conservation, community-led approaches to marine conservation, and supporting key gaps in global marine policy development and implementation.

This blog is the fourth in our In search of secret wildlife series:

In search of secret wildlife Part I: Lost fishes

In search of secret wildlife Part II: The saola

In search of secret wildlife Part III: The power of knowledge