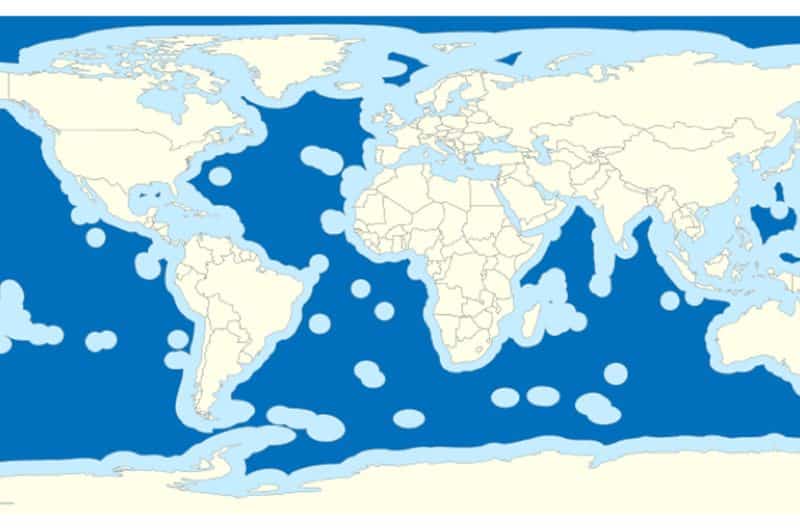

The high seas, or regions of the ocean beyond national borders, make up 50 per cent of earth’s area. They are home to a rich tapestry of ecosystems and an incredible diversity of wildlife, much of which remains undiscovered.

Yet less than one per cent of the high seas are protected, and, as international waters, there was no framework for changing that—until now.

The decision came after 36 sleepless hours. United Nations (UN) member states had hoped to reach an agreement for the protection of high seas biodiversity by Wednesday, March 1. By Saturday, consensus still seemed beyond reach.

With delegates frustrated and sleep-deprived, negotiations came perilously close to breaking down—and some feared that if this session ended without an agreement, the window of opportunity would be lost for good.

In a desperate plea, Rena Lee, the president of the conference, asked for 30 more minutes of negotiation. And miraculously, in the final hour, delegates arrived at an agreement.

Although the final agreement is not perfect, our partners recognise it as a landmark moment, not only for ocean conservation, but for the future of global biodiversity. The protracted negotiations this spring are a fitting ending for what has been an arduous journey, playing out over more than twenty years.

Two decades of advocacy for the high seas

This month’s landmark decision is the product of five years of official negotiation. But that monumental effort is itself the culmination of more than two decades of advocacy and policy work. In 2002, the UN held its first informal consultation on the protection of the marine environment in the high seas. From 2004, a series of working groups was established and began discussing the biodiversity of marine areas beyond national jurisdiction and determined that the high seas were in urgent need of conservation action.

This initial period of negotiations concluded in 2010, when the Aichi Targets—the first international goals for biodiversity—were established. Delegates recognised the necessity of conserving marine and coastal areas and called to accelerate the process towards a UN agreement. One year later, our partner the High Seas Alliance was founded. The coalition brings together more than 40 NGOs unified in their desire for a robust and actionable high seas treaty.

The high seas, depicted here in dark blue, account for nearly two-thirds of the earth’s ocean area. Image: ShareAlike 3.0

Since its founding, the High Seas Alliance has engaged in the often thankless work of international advocacy on behalf of the high seas. Through a lengthy series of preparatory meetings, and, eventually, the negotiations themselves, the High Seas Alliance helped maintain the necessary momentum to pass a robust high seas treaty.

Synchronicity Earth began funding their efforts in 2014. It took three more years for the UN to finally begin the formal negotiating process. At this point, our partner Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative (DOSI) entered the fray.

As a global network of experts, DOSI was able to present scientific evidence to policy makers who might be wary of a more advocacy-based approach. Synchronicity Earth recognised them as a vital counterpoint to the High Seas Alliance, and began funding them in 2018. Several other long-term Synchronicity Earth partners have also contributed significantly to this work, including the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, and Dr Kristina Gjerde.

During earlier negotiations, High Seas Alliance brought playful crocheted sea animals to join the movement for swift action on behalf of the high seas. Image: © High Seas Alliance.

The high seas treaty was meant to pass in 2020, but these meetings were postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In this frustrating period, flexible, long-term support for advocacy work was especially vital. Synchronicity Earth’s support helped our partners keep up the pressure on policy makers and governments through unexpected setbacks, culminating in this month’s triumphant finale to years of hard work.

What does the high seas agreement decide?

The agreement concerns four key areas of marine biodiversity management. First, it requires environmental impact assessments for any new activities expected to substantially impact the high seas. It also establishes a new body to ensure these assessments are carried out where needed and adhere to a high standard of scientific rigour.

Second, the treaty dictates that both monetary and non-monetary benefits from “marine genetic resources,” or novel inventions based on marine life, must be shared between member states. Relatedly, it recognises that lower income nations must be given the opportunity to join high seas research, and provides funding and committee oversight to make marine research more accessible.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the treaty makes it possible to establish Marine Protected Areas, or MPAs. These MPAs are vital for meeting the internationally-agreed goal of protecting 30 per cent of land, sea, and inland waters for wildlife by 2030. Crucially, a three-quarters majority will determine these areas when consensus cannot be reached, preventing single states from blocking the establishment of important conservation areas.

One key remaining question is how the treaty will interact with pre-existing marine management bodies, such as those managing regional fisheries. The treaty drastically increases transparency and accountability for these organisations, but leaves ambiguous the extent to which they will need to adhere to the new standards. The new agreement cannot directly impose decisions on pre-existing organisations. However, it does urge signatories to promote the treaty’s objectives in all their endeavours on the high seas—including as members of marine management organisations.

What ecosystems can we save?

The High Seas Alliance has outlined eight regions to prioritise as the first MPAs. These are areas of extraordinary but unprotected biodiversity and usually especially vulnerable to destructive human activity.

One is the ‘Thermal Dome’, an area in the Eastern Pacific Ocean where strong seasonal winds blow warm coastal waters into the cooler high seas. The collision forces cold, nutrient-rich water upwards, where the addition of sunlight creates the perfect habitat for a particular kind of microscopic green algae. This humble algae becomes the base for one of the most spectacular marine ecosystems on the planet.

Vast numbers of krill attract whales, dolphins, sharks, and rays. Critically Endangered leatherback sea turtle hatchlings travel through the Dome on their way to their breeding grounds. Further down, deep-water volcanoes support corals and glass sponges that can reach more than a meter high. Much more no doubt remains undiscovered.

Glass sponges are one of the many strange and beautiful creatures that call the deep seas home. Image: NOAA

UNESCO and the IUCN agree that the Dome needs urgent protection, but without the high seas agreement, there was no framework for protecting it. Today, overfishing is depleting populations, while noise pollution and ship collisions from global shipping traffic threaten vulnerable species and marine mammals.

Other potential MPAs include the ‘Emperor Seamounts’, an underwater mountain range home to 4,000-year-old corals, and ‘the Lost City’, where geothermally-heated water supports a deep-sea ecosystem that thrives independently of the sun’s energy—and perhaps offer a clue to the origin of life itself.

Though these distant ecosystems may seem out of sight, they are all crucial for human society, providing everything from climate regulation to the fish billions of people depend on. Adapted as they are to the relative calm of the deep seas, they are also highly vulnerable to disruption, and very slow, or perhaps even unable, to recover once harmed.

Without the high seas treaty, there was no way to conserve these extraordinary marine ecosystems beyond national jurisdiction. Although the fight to protect them is far from over, the path forward is clearer than it has ever been.

What comes next?

The passage of the high seas biodiversity agreement is a colossal milestone for the marine conservation movement, but it is not the end of the journey. Next, individual governments must vote to ratify the treaty. When 60 of the 193 UN member states have done so, the treaty will officially go into effect. Then, governments must rapidly and ambitiously implement it.

As we enter the ratification and implementation stage, our partners will continue to work towards speedy, evidence-based marine policy which prioritises the long-term health of our ocean. While the achievement of this Treaty is an incredible step forward, the coming years will require significant work from both governments and civil society to implement this ambitious agreement. A top priority for the High Seas Alliance is to advocate for the protection of important conservation areas as soon as possible.

Hope for the future of our ocean

In 2020, a review in the journal nature analysed past conservation efforts, and found that “a substantial recovery of the abundance, structure and function of marine life could be achieved by 2050” through coordinated efforts to mitigate human-induced pressures.

Indeed, similar efforts have worked in the past. In 1986, the international community signed a moratorium on commercial whaling. Although enforcement has been far from perfect, the treaty likely saved humpback whales from extinction.

The High Seas Treaty makes possible far more sweeping, holistic change. To truly regenerate our ocean, we must see beyond individual charismatic species, to the rich, complex marine ecosystems they rely on. As conservationists, we must continue pushing the international community to embrace robust, ambitious implementation of the treaty. It won’t be easy—but it will be more than worth it.