As many as 222 amphibian species could already have gone extinct, and 2,873 are in danger of extinction, says the second Global Amphibian Assessment, which has been published on 4 October 2023 in the journal Nature.

Our first piece covering this monument of amphibian research dives into the importance of amphibians, the key threats identified in the report, and how this research will influence conservation. This piece tells the stories behind the worst number in the report: the four amphibian species that have been lost forever.

The Chiriqui harlequin frog, Atelopus chiriquiensis. The sharp-snouted day frog, Taudactylus acutirostris. The wry lip brittle-belly frog, Craugastor myllomyllon. The Jalpa false brook salamander, Pseudoeurycea exspectata.

These are the four amphibian species confirmed extinct since the first Global Amphibian Assessment was completed in 2004. The second assessment has just been completed and published in Nature, and although the number of confirmed amphibian extinctions has only risen from 33 to 37, the real figure could be 222 (adding the species categorised as Critically Endangered, Possibly Extinct), but most likely even higher, as we do not have vast historical data on amphibian species.

Remembering the four confirmed extinct species

A male Chiriqui harlequin frog (waving) and female. Image: Aurora Gómez Espinoza

The Chiriqui harlequin frog was once locally abundant within its range in Costa Rica and Panama, and amused scientists with unusual ‘waving’ behaviour. But the reasons why these poisonous speckled creatures would wave at each other were never revealed; they disappeared due to the fungal disease chytridiomycosis in 1996. The species was finally declared extinct in 2019.

Sharp-snouted day frog. Image: Aurora Gómez Espinoza

The same fate is thought to have befallen the sharp-snouted day frog, last seen in Mount Harley, Australia, in 1997. This species was part of an ancient family of amphibians (over 100 million years old) known for having a high proportion of species with dutiful parental care, for example, carrying tadpoles in mouths or pouches. After extensive searches for twenty years failed to find this once relatively common species, it was declared extinct in 2021.

Wry lip brittle-belly frog. Image: Aurora Gómez Espinoza

Only one specimen was ever found of the wry-lip brittle-belly frog, a young female found in Guatemala in 1978. It wasn’t even given a common name; we have just translated the Greek in its scientific name, Craugastor myllomyllon: Craugastor being the genus (krauros, meaning brittle, and gastēr, meaning belly), and myllomyllon (myllos, meaning bent, and myllon, meaning lip). Myllomyllon was actually a nod to an American scientist, Jonathan A. Campbell, whose Scottish surname means ‘wry lip’. It was named after a person who never even saw it and declared extinct in 2020.

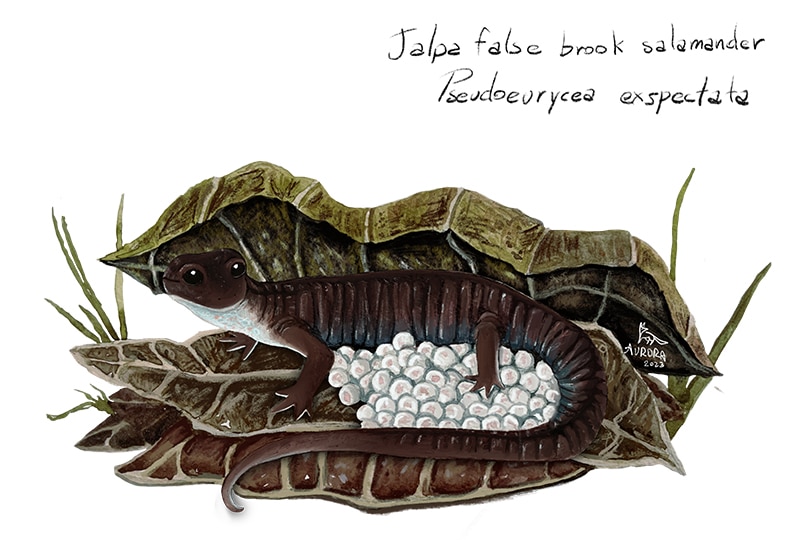

Jalpa false brook salamander. Image: Aurora Gómez Espinoza

The Jalpa false brook salamander was another species that was only ever found in Guatemala, last seen in 1976. According to a description by Jean Raffaëlli, it had a long, thin body, dark reddish-brown skin on its back and head, but dark metallic blue underneath. It had a very small known range in a forest severely degraded by deforestation and agriculture.

It may be survived, however, by its evolutionary cousin. Its appearance was notably similar to the Goebel’s false brook salamander, which was last seen in 2006 further west in Guatemala. Although this species also suffered a dramatic decline in the 1970s (most likely chytridiomycosis), and is also threatened by severe deforestation, it is thought that there are probably still micro-populations of around 50 individuals or less around its last known location.

If conservation action is taken, this Critically Endangered species may be brought back from the brink, and a close relative of the vanished Jalpa salamander may live on.

Afterword

We would like to thank Aurora Gómez Espinoza for her illustrations bringing these four extinct species to life to help tell the story of the second Global Amphibian Assessment.

Afterlife by Aurora Gómez Espinoza

When we asked her about how this project affected her, she said “It was melancholic. On one hand, I marvelled at their particularities, their attitudes, sightings, sizes, and shapes.

“But on the other hand, I felt the loss of everything that we never knew about them. It’s hard to know that we and nature lost those opportunities and now their territories are empty. That their sounds, greetings, shapes, and colours no longer accompany us…

“It is the first time that I have illustrated extinct species. Normally the content I share is promoting the conservation of endangered ones, but on this occasion, I felt a hole in my stomach with each one… it was sad.

“I hope that this sense of loss can move consciences and actions to face the amphibian crisis and address the main threats due to human activities.”

“Finally, I’m thankful and happy for the experience to collaborate with your amazing organisation, to approach this topic, and know the not-so-popular faces of what we have already lost and must keep defending. Thanks for that.”

Aurora is a socio-environmental activist who participated in the United Nations biodiversity COP15 as part of the youth delegation and is the coordinator for the Global Youth Biodiversity Network in north Mexico.