An Interview with Daniel Moss, Executive Director of the Agroecology Fund (AEF).

The Agroecology Fund began life as a collaboration between four funders, three from the US and one from Europe, who all shared the same objective of supporting agroecology. Alongside the work they were already doing within their Foundations, these funders decided that they could do better in terms of reaching deeper into the agroecology movement and sharing what they learnt if they pooled their resources. Now, four years later, there are 24 funders involved, including Synchronicity Earth.

We spoke to Daniel about his work with the Agroecology Fund, what the agroecology movement is and what it can achieve, and some of the challenges involved in making the world’s food system work for people and planet.

What is agroecology?

DM: Well, to tease the word apart, agro– relates to agricultural, cultivated landscapes, and ecology refers to the existing ecosystem, so essentially it means drawing the ‘assets’ of the surrounding ecosystems into your agricultural use. (see What is Agroecology?)

We’ve come to the point in human history where the idea of agriculture is basically to raze clear cultivated land, destroying all the soil nutrients, getting rid of what we call weeds and adding chemical inputs. In contrast, the idea of agroecology is to use local assets: key resources are soil, water, plants and biodiversity. Agroecological approaches aim to safeguard those resources and understand the complementarities between them.

The goal of agroecology is still food and fibre production, but, while for industrial farming growing food is a means to extract resources from the ground, with agroecology, the idea is that you want a flourishing ecosystem, which produces yields for consumption, but is regenerative, so the resource is sustained. In that sense, it’s the opposite of extractive industries such as mining – you’re always putting something back.

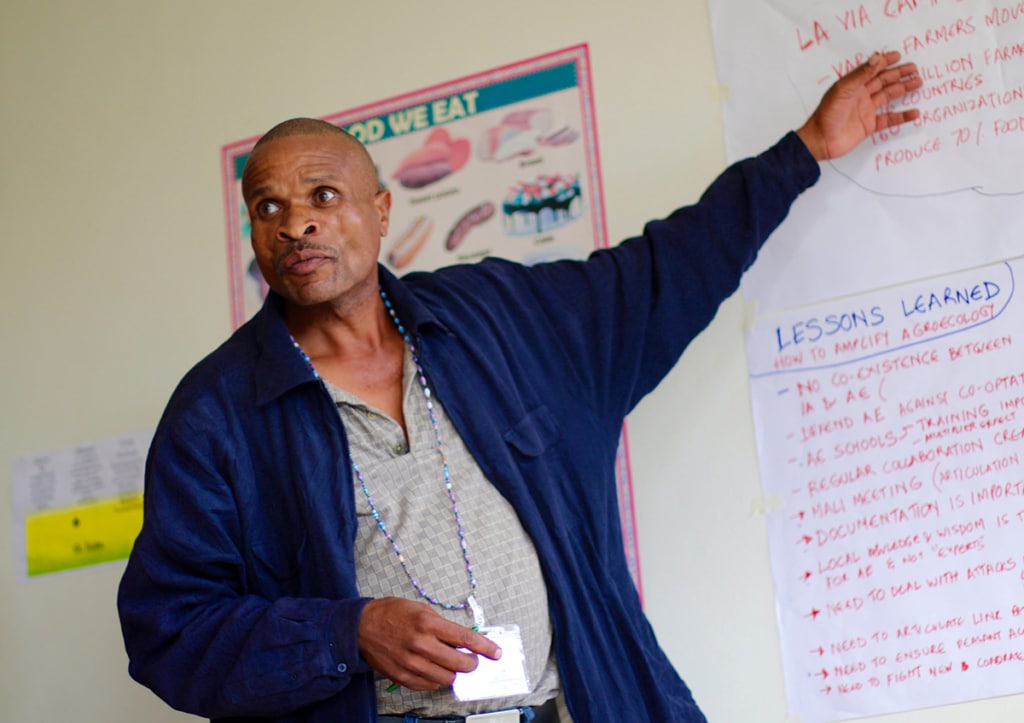

Farmer participating in the AgroEcology Fund’s 2016 Learning Exchange, Uganda. Image © Rucha Chitnis

So, is agroecology just about going back to doing things in ways that they’ve always been done, not necessarily about innovations or new ways of doing things?

DM: It is true that in the agroecology movement there is great emphasis on validating farmer knowledge – they know their crops, they know their local environments – and on supporting farmer to farmer exchange. But one of the challenges that agroecology faces is that it is often seen as a throwback or as being somehow anti-progress. In fact, while agroecology values the knowledge and experience of smallholder farmers, at the same time there’s a lot of new knowledge about the nutritional values of certain strains of rice and millet, for example, or the interaction between certain strains of plants that can provide more nutrients, and so on. We bring university researchers into these collaborations.

Agroecology works best when there is a marriage of ‘hard science’ with more ‘traditional’ types of knowledge. Farmers have often been marginalised and discredited for their knowledge, so the idea is to really uplift and to validate the farmer as a researcher, because they’re the ones that are doing the in-situ experimentation.

This is very different to the approach traditionally taken by many agriculture ministries. Agronomists were trained to disseminate knowledge that farmers required, but they were unfortunately generally captured by what’s called the ‘green revolution’, the transformation in agriculture into a high input, chemical industry. Following that approach, agronomists would come in from outside with ‘solutions’, whereas the idea with agroecology is that there are local solutions derived from farmers’ experience.

West African farmers working with Groundswell International © Groundswell International

What is the goal of the Agroecology Fund?

DM: The goal of the AEF is to amplify agroecological solutions, but that’s a bit of a mouthful! Basically, we see agroecology as providing food benefits, land tenure benefits, employment benefits and climate change benefits in the sense of sequestering carbon in the soil and protecting biodiversity. It is not just about food production, but at the most fundamental level what we are seeking is a food system that nourishes people and planet.

The Agroecology Fund appears to have a very diverse range of funders. What makes agroecology such a ‘broad church’?

DM: It’s complex and difficult, but agroecology has a lot of appeal because it is a very proactive strategy which can accomplish so many different things. I spend a lot of my time speaking to other organisations to see where the ‘sweet spot’ of their interest might lie – we have foundations that join the Agroecology Fund from very different perspectives. Synchronicity Earth is a perfect example as they are coming at the issues from more of a conservation and biodiversity angle. The interrelationship between cultivated lands and forests, for example, is a fundamental part of agroecology. Then we have other funders who approach it more from a human rights angle, which I know is something Synchronicity Earth looks at as well, but the initial point of entry is different.

Is agroecology equally relevant and important, wherever you are in the world? How does it apply to the UK or the US, for example, or is it mainly relevant to Africa, Asia and Latin America?

DM: Well, the context is very different. With all the subsidy structures in place through the Common Agricultural Policy in Europe or the USDA Farm Bill in the United States, the playing field is massively tilted towards industrial agriculture: chemical inputs are subsidised, farms don’t have to pay for all the damage that they are doing to the soil, the water system and the water table and so on. Working with a five thousand-acre corn farmer in the Midwest is clearly very different to working with subsistence farmers in Malawi, for example, who may not be market-based, they may just be trying to provide for their families. Yet increasingly those corn farmers in the Midwest are also looking for different solutions – they’re realising that the ecosystem is failing, the pollinators aren’t coming around, and there are all kinds of other issues. We need to recognise what those externalities are, better understand the negative impacts of the industrial food system and create a subsidy structure where we see the farmers as stewards of our food supply, but also of land and resources and we need to shift our investments as a community.

Then you also have the whole consumer angle, and people becoming more mindful of issues around the nutritional value of food, or workers’ exposure to chemicals. There are certainly many individual behaviours and decisions we can make as consumers, to purchase locally and so on, but there is also a political or advocacy angle to it. The difficulty there of course is, if you ask the average UK voter what they think about the Common Agricultural Policy, I’m not sure many people would have all that much to say! But there are certainly opportunities to look at how we can have a more local footprint, how to support small farmers as a fundamental part of the food supply. It’s seeing the role farmers have in safeguarding resources but also, fundamentally, looking after our wellbeing and health.

What would you say to those who argue that the current agro-industrial system has given people cheap food and that without it, we would be unable to feed the growing global population?

DM: Well, it’s kind of hard to suggest to people that food ought to be more expensive – how is that going to appear to the average consumer who might be on hard times and barely able to feed their family? But in fact, and this might surprise many people, industrial agriculture only feeds around 30 per cent of the global population. The issue here is really about the subsidy structure which has resulted in all this cheap food. Some people argue that by shifting to organic the cost would put a lot of food out of reach for the average family. However, in reality, the reason that organic food is expensive is simply because it is not subsidised – and industrial agriculture gets away with murder for not having to pay for the mess it causes to planet and people – not because it’s an intrinsically more expensive way to produce food, it isn’t.

It is critical to see where the money flows are going. I think one of the things that consumers can do is, not necessarily to get into the ins and outs of agricultural policy, but at the very least to hold large agriculture accountable for its contamination, in the same way that tobacco companies, over time, have been held accountable. There are just so many agriculturally-related contaminants now in the earth but also in our bodies, in our food, there is a plague of obesity, the list goes on.

Family farmers market in Garo tribal area, rural India. © AgroEcology Fund

Looking at the grantees for the Fund, there is a strong focus on women’s groups and movements. Why are these groups particularly important in the agroecology movement?

DM: The agroecology movement is largely based on the strengths of small farmers and small farmer and indigenous knowledge. As industrial agriculture has grown – although as commented previously is not nearly as widespread as the industry would have us believe – that knowledge has been marginalised and often scorned. This has affected women and indigenous peoples to an even greater degree. We know that a lot of farming, especially small-scale, informal ‘backyard’ farming for healthy kitchens for growing children, is done by women. In some countries, women even make up the bulk of farmers – although they may not control the assets. From the point of view of the Agroecology Fund, which is trying to advance the rights of marginalised actors across the food system, we recognise that a new food system must put their rights and knowledge front and centre. And practically speaking, women are very effective at influencing their peers and working together in common cause. We’re specifically looking for women’s rights outcomes from the agroecology work we support.

At the same time, indigenous peoples have been safeguards of ancestral food supplies for millenia and we really can’t afford to lose all that knowledge and all that seed and food diversity. It’s crucial that we strengthen indigenous organisations as we support them in building just and sustainable food systems. But, again, we have to be careful not to promote this idea that agroecology is only about the ‘old ways’ and isn’t relevant to, for example, today’s booming urban population.

How can agroecology help mitigate against climate change?

DM: People are currently scrambling for solutions to sequester carbon. Over the last couple of years in particular, there has been a lot of hard science measuring the capacity of healthy soils with a heavy organic content to be able to sequester carbon and the benefits of ‘no till’ and composting practices. There are new statistics showing that even a thin layer of compost can contribute tremendous sequestration capacity to soil. While this research is ongoing, more tools are being developed to measure carbon sequestration capacity, and those tools are important because sequestering carbon in soils is a public service and will only spread widely if we figure out a way to compensate farmers for cooling the planet. It’s their land – private land – but they’re using techniques that are favourable and beneficial to all of us. Farmers’ value to society is not just for the food they grow.

The techniques are there and the science is there, but it’s challenging because the agricultural inputs industry dominates the discourse, for example using terms like ‘climate-smart agriculture’: for them, climate-smart agriculture means laboratory manufactured seeds that are drought resistant, for example, and while that is one form of adaptation, agroecology offers more authentic and resilient climate adaptation and mitigation, techniques that are truly regenerative of landscapes and not dependent on going into debt to agroindustry.

How do you see the connections between Agroecology and culture?

DM: I was in Senegal, recently, visiting a women’s agroecology network called We are the Solution that we’re supporting in their work with a university there to identify strains of local rice that are more resilient to drought and climate change. We went to visit the local authority because the women were soliciting the city manager’s support for their work. What struck me was how aware he was of the importance of community building based around local traditions and around local foods. He had seen a large exodus of rural youth from the local area, and knew that they often no longer wanted to stay on as farm labourers working their parents’ farmland and maintaining that local knowledge and also that they were beginning to consume foods in the cities that had no connection to local food.

Here was somebody, a politician, whose job is to try to keep the community intact, but he was clearly in a difficult position. On the one hand, he expressed admiration for the women and their work to keep their communities and their culture together by reinvigorating the local agriculture and promoting local food supply, this rice in particular: at the same time he felt pressure to hand down these packets of improved seed varieties provided to him by the Ministry of Agriculture that were coming into Senegal due to pressure from international agribusiness lobbyists. He said he knew the chemical products caused economic and environmental problems, but he understood that they had a higher yield – which although a myth, is effectively disseminated by industry to convince people like the city manager that the only responsible policy option is to embrace chemical agriculture.

It was good to see that he understood the value of agroecology in a place where, for example, certain types of grains and tubers have sustained families for centuries and many are even part of rituals, or may be associated with certain rites of passage. Their use in the cultural fabric is incredibly important in terms of reinforcing efforts to preserve the biodiversity there.

I have talked to advocates and campaigners who go to talk to ministers to present an argument about agroecology and they find you can present all kinds of statistics about carbon sequestration and so on, but frequently the best tactic is to ask the minister about a favourite dish their grandmother used to cook! This is often the most effective way to re-establish that connection back to where he or she comes from and help them understand what needs to be preserved. There’s no doubt that the migration issue is for so many reasons a disaster, and losing food traditions is one of the real problems caused by migration to the cities.

A Khasi seed saver in Northeast India working with the North East Slow Food and Agrobiodiversity Society © Agroecology Fund

What are the obstacles to greater adoption of agroecological approaches?

DM: This issue of youth unemployment and migration is a big one. If you go to a meeting of practitioners and advocates of agroecology, you’ll often meet mostly older community members. They will tell you about the reduction in the number of young people now choosing to stay on the farms, so there has to be more emphasis on the entrepreneurial opportunities for young people. If we cast agroecology as an anti-technology solution, we’re going to lose the youth very quickly. So, an important part of the work that we are starting to do inside the Agroecology Fund is supporting small-scale, profit-making agroecological enterprises as well. If you want to reduce the amount of imported food people buy at the local supermarkets, what are the alternatives both from a production and a marketing point of view? We have several foundations that are interested in using their endowments for the purposes of investment in alternative businesses, particularly for young people, and that has great potential.

Another obstacle is that, broadly speaking, most countries’ investment in agriculture has diminished overall, with so-called structural adjustment and countries having to shrink the size of their public sectors as they run into debt. The challenge is to scale up agroecology, but: where is the public money to support research and extension? How is it going to achieve critical mass?

I think this is where it is so vital to build these farmers’ organisations and farmers’ networks – a more horizontal network. For this to work, you need a greater number of capable organisations. Part of what we fund through the AEF are agroecology schools, as farmer organisations see the need to develop a knowledge base and develop a system of multiplication and dissemination.

Nelson Mudzingwa of the Zimbabwe Smallholder Organic Farmers Forum, a Via Campesina affiliate, discussing his work. © Rucha Chitnis

How has the support of Synchronicity Earth contributed to the development of the Agroecology Fund?

DM: Synchronicity Earth contributes to our work in a couple of key ways. One is through the funding they have provided since early on in the founding of the AgroEcology Fund, which has been critical to grow our pool: The strength of the AEF is based on the accumulation of all the donor contributions. The other key thing, I think, is that, as I mentioned before, we have different points of entry for different funders and Synchronicity Earth’s perspective around conservation and biodiversity is critical. I think that the AEF as a community works better when funders are sharing their points of emphasis because agroecology by nature cuts across issue areas, seeking allies for the multiple public benefits it provides. Synchronicity Earth has had an influence on other foundations in terms of seeing agroecology as critical to conserving biodiversity in some of the places where it is most threatened. The Fund has a very participatory governance structure and Katy (Scholfield) serves on the Executive Committee, which is hugely helpful, as it’s a volunteer-led effort. I’m a two-thirds staff person and then the rest comes from the efforts of our volunteers – we have advisers and we have donors, so Katy takes one of those seats as a donor.

What gives you hope and optimism in 2019?

I really feel that there is a lot of momentum around this idea of transforming the food system, a lot of awakening around the various things we talked about, especially the capacity for agroecology to play a key role in healthy diets and healthy land, to nourish both people and planet.

I think we’re also seeing the emperor being exposed with no clothes! There is more and more reporting and research on the threats posed by agroindustry and all the negative externalities of the industrial food system. I do think people are starting to focus more attention on this and, the more dire the situation gets, the more opportunity there is for agroecology to show itself as a solution. But really at the end of the day what gives me most hope is these organisations, the grantees we support that are just doing very interesting, very important, very complex work with their constituencies and trying to influence policymakers. They are not always successful, but they often are, and that gives me great hope for the future.

Synchronicity Earth has supported the Agroecology Fund since 2014. Find out more