Over the past 18 years, Dr Grace Iara Souza has developed a deep understanding of the impacts of global environmental governance and social policies on local rainforest defenders in the Brazilian Amazon. Her academic training is rooted in Political Ecology, and her professional experience includes project management in the educational, private, and charity sectors, teaching in higher education and researching environmental conservation and development.

Grace spends some of her time advising Synchronicity Earth as our Latin America affiliate. Her knowledge and experience working with conservationists and policymakers in Brazil and Latin America provides a vital bridge, both in terms of knowledge and culture, between our partners on the ground and our London-based team. In this interview, she speaks to Jim Pettiward about her pathway into environmental conservation.

Can you describe how you came to be working in the environmental sector?

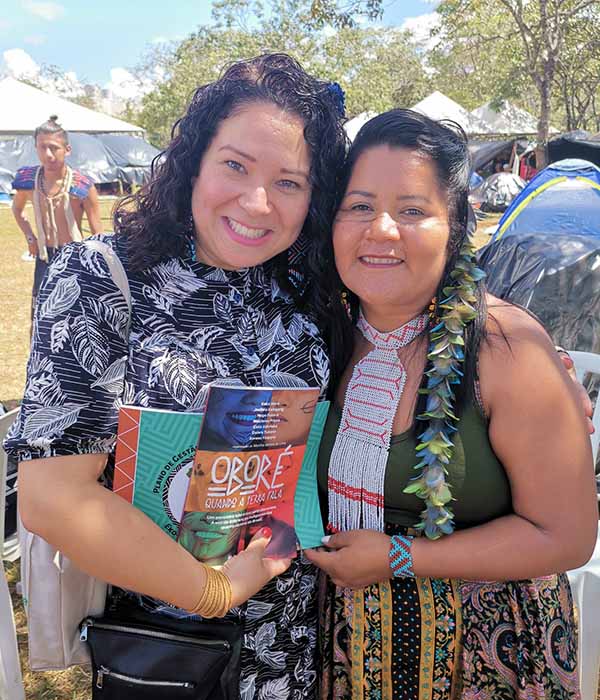

Grace Iara and the Guarani leader Kerexu Yxapyry at the Indigenous Free Land Camp (ATL) 2022

Grace: My introduction to environmental conservation began when I was working in the private sector for the fourth-largest producer of sugar and ethanol in Brazil. That was back in the early 2000s, and the company was looking into producing carbon credit certificates in line with the Kyoto Protocol. I spent a lot of time researching the theme and preparing the team for all the phases of the Clean Development Mechanism certification, which meant travelling around Brazil to get a feel for what was happening in different regions.

At that time, I was also studying International Relations, but I found that rather than foreign trade, my main interest was in the relationship between what was happening at a local level and global policy and governance systems. But it was only once studying in the UK and being exposed to a more critical view of environmental history that I started to develop a more critical understanding of global governance and offsetting initiatives like carbon credits (or ‘licenses to pollute’, as I call them).

In 2007, I moved to the UK to study English, and I ended up going on to a master’s degree on Environment, Politics and Globalisation at King’s College, London, in 2010.

As my knowledge developed, I began to understand there was something wrong with the whole concept of offsetting carbon emissions.

Countries and companies with higher greenhouse gas emissions have been doing little to reduce their contributions to climate change and it is unfair to the planet and biodiversity-rich countries to provide ‘licences to pollute’ when they are the ones most impacted by deforestation, pollution, and the impacts of climate change.

I knew that the best place for me to carry out my master’s research would be in the Amazon. At that point, I was one of those ‘paulistas’ (resident of São Paulo), a Brazilian who had to leave Brazil to really see Brazil. I had grown up inside the country, but my understanding was limited by the social mobility and privileges of living in the country’s business capital. This added to how little I’d seen of the multiple versions of Brazil and my vision of the world back then.

I felt I needed to see how local people in the Amazon understood the profound importance of the rainforest and its role in global human security. I started looking into the idea of the ‘internationalisation’ of the Amazon. And once I was there, I realised the price local people paid by being a part of a global natural resource, something vitally important to global human and environmental security.

From that moment on, the way I perceived the world changed, particularly in relation to concepts such as wealth, development, and security. I realised I needed more time in the Amazon and that was when I decided to study for a PhD.

Visiting Synchronicity Earth partner Instituto Juruá in 2022

What was the focus of your PhD?

Grace: I studied Political Ecology. During my PhD, I spent some time living with Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in communities along the Black River (Rio Negro), a tributary of the Amazon river.

I also spent time with the people who were engaging with policy implementation for protected areas. I interviewed conservation decision-makers at local level, as well as those who were involved in global environmental agreements to conserve the Amazon, and NGO workers following and working at national and local levels. I was keen to understand how these big commitments by G7 countries and the various global agreements translated to the national, and then local contexts.

Political ecology seeks to understand the power dynamics between a vast range of stakeholders: it’s a set of lenses through which to see the world. The lenses I was most interested in were the post-colonial context and forms of resistance, but also politics of scale. Who should be protected? By whom? And at whose expense?

I wanted to explore the role of conservation within the political economy. For example, what motivated the G7 to have a project to conserve forests, starting with Brazil? What role does Brazil play within this political economy, in which their forests are one of the elements of a global discussion? And this was also when I began to understand that conservation is not necessarily decided based on biodiversity, per se, but on a political agenda.

What were the biggest takeaways from your PhD?

Grace: It is a real privilege to be able to see things from several different perspectives together and to understand the connections between the social and the environmental and how these elements all fit together into one big puzzle. And being aware of that, to realise the impacts of what is really happening on the ground.

From the start, it was hard not to focus on the problems, but I decided there was more value in concentrating on the resistance and what flourished based on that.

I understood that local and personal commitments are what really matters in the process of conservation. It is these everyday forms of resistance and the everyday relationships between rainforest people, between park and protected area managers, the social contract between them and what they make happen, and their ability to adapt, that can bring about real change.

Co-teaching with Dr Charles Palmer (LSE) & Dra Edilza Laray (UEA), River Negro- Amazonas, 2018

For instance, many of the people formally involved in environmental conservation in the Amazonian region come from outside of Amazonas, so they arrive with a timeframe and an understanding of the world that is different from the reality on the ground. However, once they stay there, and relationships are formed, conservation takes a completely different form. It becomes more inclusive of traditional knowledge and the need to embrace and support the participation of local people in conservation policies.

In terms of my personal journey, my studies led me to question how I could use the knowledge that I had been given – the gift I had received from so many people opening their doors, welcoming me into their houses and their families.

How could I use that knowledge in a way that would not stay locked away on a shelf in academia? How could I use my knowledge and experience so other people would be able to engage with it? That became a constant question and challenge for me.

So how did you begin to answer that question?

Grace: Firstly, through academia – lecturing at university, co-creating knowledge with other people and sharing what I’d learnt of global/national concepts of conservation with the people I met – students, colleagues, at conferences and so on. But at the same time, I was wondering how I could be of greater service in a way that is effective given the urgency of the times that we are living in.

It was while I was lecturing in Political Ecology at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), in London, trying to bring a critical approach to the conversation, that an event called Flourishing Diversity Series took place at University College London (UCL).

The Flourishing Diversity Series brought Indigenous Peoples from across 17 countries to London, including representation from the Ashaninka, Puyanawas, and Guaranis from Brazil. That was at the same time that the fires in the Amazon and other biomes were on the cover of every international newspaper. Several organisations concerned about climate change and environmental justice got together in response to a call for international solidarity and commitment. I have been lucky to be part of this Alliance.

What are the most significant challenges currently facing locally-led conservation organisations in Brazil and how can partners overcome some of those challenges?

Grace: The context in Brazil is extremely challenging. It was eye-opening and distressing to see the kinds of things our partners have been facing from one day to the next: retaliation from local authorities; a building contractor that wants to increase the size of their development, and feels they can act that way with impunity, which is actually true considering the lack of conservation and control measures in the past four to six years.

It’s common to see tourism developments not taking into consideration a protected area, park, or the communities that live around them. But it’s also true to say that this is not a uniquely Brazilian problem.

The interrelationships between society and nature are taken for granted almost everywhere. Many people simply do not see or acknowledge that the lack of rain or the wildfires has anything to do with the trees that are being cut down, or the diminishing size of protected areas. It’s a very short-term way of thinking: short-termism is embedded in cultures across most of the western world.

But at the same time, these challenges are also fomenting a strong desire among the partners I visited to connect more and strengthen connections with other local groups and projects so they can flourish and be more resistant and resilient in achieving what they set out to do.

How much is what is happening on the ground starting to feed more into environmental policy-making at a higher level?

Grace: Things are slowly moving on the ground: this might be the conservation of a protected area that used to be a ‘paper park’, but that is gradually being properly implemented; or the recategorisation of a park to become a sustainable use protected area – or even just in the acknowledgement of the presence of local people there; or it may be through something people call ‘payment for ecosystem services’ being renegotiated constantly on the ground to incorporate local people; or even a broader global environmental agreement.

Celebrating the passing of the Motion 129 (WCC 2020 Resolution 129) to protect 80% of the Amazon by 2025 with COICA at IUCN 2021

But none of this is happening enough, or quickly enough. These processes often involve decision-makers who have never been to the region, who may not understand or acknowledge the voices and experiences of local people or the knowledge of the protected area managers who have taken time to observe and build relationships with the local community.

Something which adds to the challenge is what seems to be a constant desire for novelty.

In the academic world, you often only seem to get noticed when you bring something novel or different. Likewise, in conservation, or policymaking circles, there is often more focus on trying to find something new, or ‘innovative’, rather than trying to implement what has already been agreed.

This desire for novelty can mean that all the solutions that already exist are simply ignoring the fact that relationships take time to build, and policies take a long time to implement.

Which elements of Synchronicity Earth approach do you value most? What role can and should we play?

Grace: I love the fact that Synchronicity Earth is very open to listening to its partners and approaching how they can work together without a set agenda, listening to and learning with them.

I think Synchronicity Earth understands the importance of providing core support, of listening and being guided by the groups and communities they are supporting. So, rather than Synchronicity Earth and other partners like the Alliance creating an agenda and trying to dictate what grassroots organisations, Indigenous Peoples and local communities should be doing, the default position is to constantly listen and understand how best to support resilience and resistance.

And by doing that, we intensify and help to create stronger communities that are better equipped to deal with the many challenges they face.

Visiting the Guarani NhuPorã tekoha (village) with Curicaca’s team, in March 2022

What can people living in a rich, industrialised nation in the Global North do to help support Indigenous Peoples to protect their territories?

Grace: Whenever I introduce myself and tell somebody where I am from, I often hear things like “Oh, my God, your government is destroying the Amazon!”.

It’s very rare to hear someone say, “Oh, my God, this well-known high street bank, or that well-known supermarket is destroying the Amazon”, or to hear them question how their own political leaders and policymakers are contributing to that destruction. But what if we thought more about what we are accountable for and what we are committed to?

There are many different things an individual can do. Not just the usual things in our personal choices: becoming vegetarian or vegan, thinking more about our environmental footprint and so on. We can also be more curious and question more. Question our MP about the traceability of trade in the UK. Is it OK that our university, bank, or pension scheme is propping up the fossil fuel industry? How much do we know about UK environmental legislation? Do we just sit by while water companies pump sewage into our rivers and seas? How can we pressure our local MP, question our bank, change our pension schemes, or find out where the food in our local supermarket comes from? There’s plenty of information out there about companies linked to deforestation and multiple other destructive environmental activities that are impacting areas of incredible biodiversity around the world – all you need to do is engage your curiosity.

For me, all these questions are connected to the idea of ‘geographies of care’. How can I care from where I am, use any power I have, my social mobility, to promote change, so I am not importing deforestation, regardless of who is in government in Brazil? How can I engage with environmental policies here or in Europe?

We know what is happening, so how can we contribute to changes in, for example, legislation where we have more influence and leverage? There is so much we can do on an individual basis, if we just engage our curiosity and really think about what matters to us.

Finally, I imagine the overwhelming emotion after the recent election results in Brazil must be relief?

Following Luis Inácio Lula da Silva’s election victory, there is definitely a strong feeling of relief and hope amongst many people in the country. In stark contrast to the previous administration, nationally we are hoping for strong commitments to environmental justice, human rights, and indigenous and Afro-descendant participation in the country’s policymaking and implementation. As a strong diplomatic leader, we can also expect Lula to promote these values across global governance too. But it is important to be aware that this transition will not be swift or easy. The country is divided, the economy is fragile, and there will be much resistance to change within the elected government.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity