Fishing for human consumption is thought to be the biggest driver of biodiversity loss in our oceans, according to the recent Living Planet Report by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Zoological Society of London (ZSL). Seafood is an important part of the diet of more than 3 billion people, and fisheries and aquaculture provide employment for around 60 million. However, our global fisheries are not sustainable. One particularly alarming forecast published in the journal Science in 2006 predicted that the world would run out of wild-caught seafood by 2048.

However, governments around the world are paying subsidies to keep unsustainable, industrial fisheries operating in the oceans, fisheries that would otherwise be financially unviable. How can this be? Anna Heath explains.

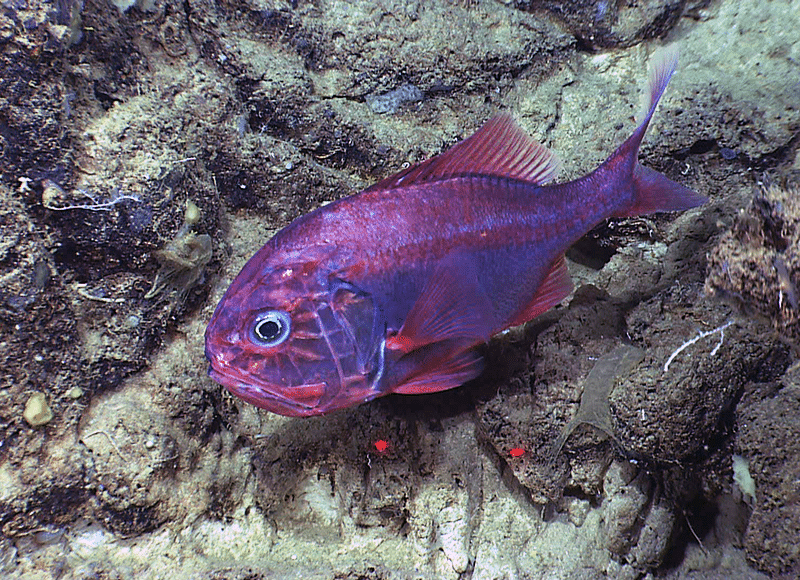

Far off the east coast of New Zealand in the wild and remote waters of the southwest Pacific Ocean, there is a collection of colossal under-sea volcanoes which act as magnets for marine life. Rising up from the seafloor, these ‘seamounts’ are renowned for supporting a vast array of deep-sea species, many of which cannot be found anywhere else in the world. One particular fish which calls these seamounts home is the orange roughy, or ‘slimehead’ as it was once known (thanks to its special ability to ooze mucus from canals in its head). This extraordinary fish, like many deep-sea creatures, lives life in the slow lane – it is estimated to live up to 150 years old, and does not reproduce until it is 20.

It is across the surface of this unique habitat that massive deep-sea trawlers are dragged, targeting large gatherings of the highly vulnerable orange roughy. The slow and drawn-out life cycle of this fish means that its populations collapse quickly, and the high levels of bycatch (accidental catches of non-target species) associated with trawl fisheries mean that it is not even just the orange roughy, but countless other species that are destroyed for the sake of this catch. But the real kicker, and the focus of this blog, is that the vast majority of deep-sea trawl fisheries such as this one would not even be profitable without the subsidies they receive from governments.

Orange Roughy, one of the most commercially fished deep-water species. Orange Roughy can live for around 150 years and do not begin to breed until they are around 25 years old, making them extremely susceptible to over-fishing. Image: NOAA OKEANOS EXPLORER Program, Gulf of Mexico 2014 Expedition.

Tax payers’ money funds marine destruction

That’s right, you didn’t misread that: governments of countries around the world are using tax payers’ money to fund the mass destruction of marine life, to the tune of around USD 35 billion per year. This is estimated to be equal to 30 to 40 per cent of the total value of fish caught globally each year. At first glance, this may seem like a good thing. Fishing is an important source of revenue for coastal communities around the world, and these subsidies may be supporting cultural traditions and protecting small-scale fisheries from the financial insecurity of relying on unstable fish stocks. However, an astonishing 84 per cent of fisheries subsidies are estimated to go to industrial fisheries. This means that rather than supporting small-scale fisheries, the majority of subsidies are instead paying for industrial fleets to deplete the resources relied upon by millions of people globally (see this film by the Environmental Justice Foundation on how industrial subsidies have impacted artisanal fishers in Ghana). Subsidies which go towards increasing the capacity of fleets to catch more fish are very aptly named ‘perverse’ fisheries subsidies – these make up nearly 60 per cent of subsidies given out globally.

It has been widely recognised that fisheries subsidies are a key driver of global overfishing, to the point where eliminating ‘harmful’ fisheries subsidies by 2020 is a goal under the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals. However, due in large part to the complexity of why fisheries subsidies exist, little progress has been made towards this goal.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), most tuna stocks are fully exploited (meaning there is no room for fishery expansion) and some are already overexploited (there is a risk of stock collapse). Image: UN Women/Ryan Brown

Why do they exist?

In looking at these figures, it seems very clear that the maths just do not add up. In a world where profit comes before almost anything else, how was such a financially unprofitable system developed, and how has it been allowed to continue for such a long time? And it has been a long time – early examples of fisheries subsidies date back to the very first presidential administration of the USA. In delving into this question, I soon realised it would take a lot more than a few lines in this blog to unpack this issue, but a very brief summary will hopefully help to put this in context.

In essence, fisheries subsidies are a result of a complex cocktail of economic, political, social and historic factors, combined with a fundamental lack of data. Examples of why fisheries subsidies have been put in place range from maintaining a resident fishing population in the northern reaches of Norway, to promoting in-country rather than foreign fishing in national waters in the USA, to China and Russia wanting a political presence in Antarctic waters.

A fundamental reason for the persistence of fisheries subsidies is that fisheries are ultimately competing globally for the same limited resource. One government is therefore unlikely to limit subsidies, which would make their fleet uncompetitive, if other countries do not agree to do the same.

The notorious power of industrial fishing lobbies around the world, along with the fact that fishing is one of the only ways for a country to have reach and influence in marine territories, mean that decisions around fisheries subsidies are very rarely taken based on economics alone, or even at all.

A fishing trawler is a commercial fishing vessel which drags a trawl fishing net along the bottom of the sea or in midwater at a specified depth. They can cause huge amounts of damage to the seafloor and often catch a lot of things they’re not trying to catch (bycatch). Image © Shutterstock

International agreement

The deep connection between fisheries subsidies and international relations means that it is important that some regulations are put in place on fisheries subsidies at an international level. However, this is much easier said than done, and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has now been debating regulations on fisheries subsidies for two decades. As I have heard a senior negotiator at the WTO say, if the debate on fisheries subsidies were a child, it would now have left home, learned to drive and be able to drink alcohol.

However, in 2017, thanks in part to the work of Synchronicity Earth partner BLOOM Association (BLOOM), the WTO made a historic agreement. This was actually an agreement to come to an agreement on fisheries subsidies, which doesn’t sound like much, but it was the first ever agreement in a legally binding structure on fisheries subsidies. The WTO has already missed its own 2019 deadline for this agreement (and the UN deadline on eliminating harmful subsidies by 2020), but it has said it is committed to concluding this by the end of the year. If it goes through, this will be an unprecedented step towards curbing fisheries subsidies.

Ghost nets (abandoned fishing equipment) are another side effect of the global fishing industry which are a major contributor to the ocean plastics crisis and continue to entangle sea life after they are discarded. Image © Shutterstock

We don’t know the half of it

A critical issue running alongside the global politics of fisheries subsidies is that what is paid out by each government is shrouded in secrecy. The majority of governments do not report the subsidies they give out to the fisheries sector, meaning that much of the knowledge we have on fisheries subsidies globally is based heavily on estimates. This makes it incredibly challenging to hold any particular government or industry to account.

Filling this knowledge gap is a key element of the work of Synchronicity Earth’s partner, BLOOM. BLOOM has a strong track record of delving deep behind the scenes in government records to bring to light where subsidies are really going. For example, in 2018, BLOOM discovered that over EUR 5.7 million had been spent on the development of an industrial electric fishing fleet in the Netherlands (a fishing method that electrocutes fish in the water). Even worse, this had been agreed under the guise of it being ‘innovative’ gear rather than an incredibly destructive one. BLOOM was able to use this research to successfully campaign for a ban on electric fishing in Europe, which was agreed in 2019.

Another difficult aspect of trying to keep fisheries sustainable is regulation. Fisheries observers travel aboard fishing vessels, tracking catches – including any bycatch of endangered species – in order to preserve fish stocks, but it is an extremely dangerous occupation. Image © Shutterstock

An overlooked challenge

Despite the far-reaching and strongly negative impacts of most fisheries subsidies, this is an area where only a small handful of organisations is working. Unlike some marine conservation challenges, where a clear solution and path to recovery can be identified and followed, the problem of fisheries subsidies is one where very few interventions have seen any success.

This is daunting, and incredibly challenging, but we see this issue as one that presents high risk, but also very high reward. It has been encouraging to see, over the past couple of years, an increasing number of organisations and voices engaging in the push towards the elimination of harmful fisheries subsidies, and we remain optimistic that progress will and must be made on this in 2020.